In my article – Disappearance of the Ninth Legion – I set out to address the probable fate of the famous Roman Ninth Legion – the IX Hispana –which mysteriously disappeared early in the 2nd Century AD from the historical record. In so doing I challenged the prevalent view these days that the legion must have been defeated in battle somewhere other than in Scotland.

The assumption that the legion was lost out with Scotland (the legion was then stationed in Britannia) has since the 1970s become fashionable, an anomaly attributable to the persuasive power of constant repetition by a vocal minority. However, there is no quality evidence – either artefactual or epigraphic – that supports these pieces of guesswork, a state of affairs that makes them simply smack of wishful thinking.

On the other hand in my Eagle of the Ninth article, I looked closely at the epigraphic references which the ancients themselves made of these times; tantalising records giving glimpses of endemic warfare with the tribes of ancient Scotland and Rome’s setbacks with noteworthy troop casualties here in the troubled years of the early 2nd Century AD.

Rather tellingly this all occurs around the same period of time as the last accepted surviving artefactual and epigraphic record of the Ninth Legion in the archaeological body of evidence. Now this is a sounder basis to work with.

Since 2007 two things have happened:

First: Roman Scotland identified the likely site of the battle of Mons Graupius (83 AD) at the Clevage Hills next to Dunning in Strathearn in 2009. This has been well received due to the methodical approach adopted to analyse competing sites. It demonstrated that we can still attempt to identify the site of otherwise “lost” actions in history with good probability if we look at all the available information methodically and – most importantly – evenly.

Second: two movies at the time of writing are currently in production whose plots revolve around the Ninth’s loss in Scotland. Good….and frankly long overdue! Clearly, we do not yet know the quality of these movies however anything that promotes among Scots a consciousness of Rome’s activities in Scotland can only be a good thing, and, will help put paid to the all too prevalent myth that the Romans stopped at Hadrian’s Wall, never venturing north thereafter.

The first film; “Centurion” by writer/director Neil Marshall is potentially set to follow the horror genre employed in “Dog Soldiers” and promises to be an enjoyable light-hearted romp. Filming has taken place in and around the Glenfeshie Estate in Inverness-shire which in itself however is a bit of a cause for concern.

The second film “The Eagle of the Ninth” is currently receiving headlines as it has signed up a brace of well-known actors. It is directed by Kevin MacDonald and is set to bring Rosemary Sutcliffe’s well-known 1954 novel to the big screen, a long-awaited airing since the – now cult – BBC serialisation of 1977 was inexplicably never re-screened. It is little wonder therefore that nearly everyone we meet in the field is avidly discussing these new films.

Indeed Roman Scotland friend Jim Brown from Heddon on the Wall has gone one step further and challenged us to find a possible site of the legion’s loss in Scotland (or at least north of Hadrian’s Wall) using the same methodical approach we used in the Mons Graupius search.

This did not take much persuasion. Our Eagle of the Ninth article originally set out to challenge the prevalent theories noted above for the legion’s loss somewhere (frankly anywhere) other than Scotland. However with Scots interest in this period thankfully growing now is the right time to speculate on what could have happened and remind many doubters that the Romans were indeed active in Scotland in the years in question.

Why?

Well, the films for cinematic effect will no doubt sow yet again the vivid Hollywood ideal of scenic and mountainous highland landscapes in the public consciousness of all things concerning Scotland – filming has already taken place as mentioned above in Glenfeshie in the Cairngorms.

It should be remembered however that the Romans appear never to have set foot within the Highland massif in strength.

And surely we must set our mark in writing now before the films receive the almost inevitable hoots of derision from the usual academic suspects, a reaction that yet again will merely confuse the debate over the legion’s probable loss in Scotland.

So now is the best time to present a possibility. By using a similar approach to that used in our Mons Graupius article we can suggest a possible setting – here in academically maligned Scotland – for the legion’s last march and its ominous terminus.

In my Mons Graupius article, we looked at four key factors when analysing a hefty list of sites competing for the honour of being recognised as the scene of that battle. These were:

- The Primary Sources; i.e. what the ancients themselves wrote,

- The Archaeological Source; i.e. relevant remains surviving on the ground from antiquity, in this case marching camps,

- A Practical Analysis of the Sites; investigating any given location’s strengths and weaknesses in a manner devoid of preconceived ideas or partisan bias,

- The name “Mons Graupius”; some very few place-names still exist which can be traced back to names recorded in antiquity.

Clearly, in the context of the search for the Ninth, we have no detailed commentary available to us like Tacitus’s “The Agricola”. Nor do we have a name for the place where the Ninth Legion was lost, so we are unable to consider modern names and analyse the applicability of their likely ancient antecedents.

However, locating the site of Mons Graupius was no easy task. We are not therefore disheartened by academic’s remarks that “we know nothing of these times” as fortunately, that is far from correct.

So what are the “factors” available to us in our investigation over the loss of the Ninth?

These are:

- The primary written sources from antiquity,

- The archaeological source in the shape of marching camp remains.

Further, we will consider the tribes known to have been in conflict with Rome as well as casting a canny eye over the landscapes that these factors point towards.

The Primary Written Sources

We do not have Tacitus’s remarkable work the “Agricola” to rely on, however, it should be realised that the survival of such a detailed account into modern times is a fabulously rare occurrence, indeed a great boon for the study of the early Roman period in Scotland as a whole.

The vast majority of ancient texts relating to ancient times are much shorter and fragmentary. It is common practice for historians to relate many of these different sources from similar periods together to help “build the bigger picture”. In this, we are fortunate to have the short – but relevant – surviving remarks from Juvenal, Spartianus and Cornelius Fronto.

These ancient soundbites taken as a whole begin to paint a telling picture of the period we are looking at, and they remain the unique point of reference anywhere for the search for the lost Ninth.

What are these ancient sound-bites?

Aelius Spartianus

Aelius Spartianus (probably late 4th C AD) is the author of the biography of the reign of the Emperor Hadrian (117- 138 AD) in the Scriptores Historiae Augustae. This early section of the SHA is considered reliable, often directly quoting the respected 3rd-century AD historian Marius Maximus.

In chapter 5 of “The Life of Hadrian” Spartianus wrote:

“On taking possession of the Imperial power Hadrian at once resumed the policy of the early emperors, and devoted his attention to maintaining peace throughout the world. For the nations which Trajan had conquered began to revolt; the Moors, moreover, began to make attacks, and the Sarmatians to wage war, the Britons (sic) could not be kept under Roman sway”.

As there are no signs of disturbances by the indigenous tribes of Wales and England this can only be a reference to the lands of southern Scotland from which the Romans had only recently been forced to withdraw but which they probably still considered to be nominally under Rome’s control.

Cornelius Fronto

Cornelius Fronto (100 – 166 AD) was an orator from Cirta and lived through the period we are looking at as a young man. Some of the letters he later sent as an old man to the Emperors Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus (dateable to the early 160s AD) survive. That of interest to us here is a letter he sent to Marcus, consoling him over Roman losses in the east early in his reign (161 -162 AD):

“…. And again when your grandfather (became) Emperor, how many soldiers were killed by the Jews, how many by the Britons?”

Decimus Iunius Iuvenalis (Juvenal)

The poet Juvenal (late 1st – early 2nd Century AD) – author of the Satires – makes a tantalising side reference to war in Britain around 105 AD. Here he refers – in Roman upper-class salon talk – to the barbaric antics of the tribal chief Aviragus in the then-current troubles in the south of Scotland.

This slightly precedes the events of 117 AD but – when taken with the archaeological body of evidence of destruction in southern Scotland and along the Stanegate in 105 AD – it assists in painting a tantalising picture of the troubled years immediately preceding Hadrian’s ascension to power in 117 AD.

The Archaeological source; marching camps.

Scotland has the finest tally of marching campsites known anywhere. This is an archaeological legacy of ongoing warfare spanning over three hundred years. With improved technology, the list will undoubtedly increase as further camps come to light.

These marching camps were the overnight bivouacs of Roman armies on campaign. Such a great number of these survive in Scotland that it is possible – once a few basic rules of “camp morphology” are understood – to attempt to track the progress of specific ancient armies on campaigns.

How can we do this?

By analysing both the size (which suggests the likely number of troops the camp may have contained) and morphology of the camps layout (which helps define certain general periods of likely use based on known archaeological structural site sequences elsewhere in Scotland) we can begin to suggest relationships between those camps currently known.

This can be done with reasonable conviction even between camps spaced quite far apart. These are the fragmentary remains of the once-mighty chains of camps which marked the progress of many Roman armies on campaign in Scotland. Those camps in between these known ones either remain to be discovered or are lost forever under modern development or the abrasive action of the plough over the intervening centuries.

This is an incredibly fruitful – if speculative – line of enquiry; one where we feel Scotland – not least with recent success identifying Mons Graupius – should and can be at the forefront.

Those tribes with a track record of conflict with Rome

Common misconception envisages the Romans combating only those tribes of Scotland’s northernmost reaches. This is fundamentally incorrect.

By setting aside such preconceptions and relying instead on what the primary literary sources from antiquity tell us (over a considerable period it should be pointed out) we can glean a fair understanding of which tribes were frequently at odds with Rome’s hegemony in the British Isles.

This gives us another extremely potent line of investigation.

Further, sufficient -if incomplete – knowledge is available from ancient cartographers to give a reasonably good picture of the distribution of the tribes of ancient Scotland.

How does this help us?

It enables us to focus on marching camps which sit in the problematic lands of those notably intractable tribes. Using camp morphology we can further refine our search to those camps of a size and morphology which is of interest. Finding relationships between any such camps allows us to suggest a sequence and route as well as – most importantly – speculate the forces’ planned destination.

A practical analysis on the ground

It is absolutely imperative that a quest like this is undertaken out in the countryside, not as an abstract academic exercise within the cloistered comfort of a Classics Department.

A keen eye able to read the ground will never go amiss, indeed such skill will be crucial in identifying that most difficult terrain where the Romans are factually known to have gone; not the scenic mountainous Highlands which Hollywood would have us (incorrectly) believe to be the setting for all interaction between invaders and the peoples of Scotland throughout the centuries.

What sort of conflict should we be looking for?

The lack of any further definitive records of set-piece pitched battles between native and Roman after Mons Graupius (83 AD) strongly suggests that the tribes learnt the lesson from that fateful encounter. Roman organisation, training and discipline usually gave them the advantage in traditional set-piece confrontations, a situation the tribes appear to have recognised after Mons Graupius.

Indeed it was recorded over a century later (Cassius Dio and Herodian on Severus’s 209 AD Scottish campaign) that the tribes successfully fought the Romans and inflicted serious casualties using hit-and-run tactics; a manner of taking on Rome with a greater likelihood of success.

An ambush therefore on a Roman column toiling through difficult terrain, or alternatively a nocturnal assault on their marching camp (the Caledonians it should be remembered almost succeeded against the same legion in 82 AD under just such circumstances) is the best scenario to explain how the tribes may have engineered the circumstances where Rome’s battlefield superiority could be neutralised and tribal success best guaranteed.

So where did the events take place and how do our 4 factors noted above fit in?

Clearly, the records made by Juvenal, Spartianus and Cornelius Fronto are sufficient to warrant the hypothesis we made in our Eagle of the Ninth article (link). This made two assumptions;

First; that the legion may have ventured north at less than full strength – allowing a plausible explanation for the existence for those very few individuals in later years who are claimed at some time in their lives to have been members of the Ninth.

We suggested therefore that perhaps as many of two of the legions cohorts could perhaps have been on vexillation service on the continent – a particularly common occurrence for the legion based in York, while it is reasonable to suggest that at least one cohort (perhaps even the double strength first cohort) may have been left as a skeleton garrison in the legion’s fortress at York.

There is, of course, no direct evidence from antiquity telling us this, or indeed contradicting it, this is merely speculating towards a working hypothesis but one that we consider is compelling enough to merit further investigation.

The legion at full strength will have mustered somewhere between 5,200 and 5,500 men. The equivalent of 3 cohorts taken out of the equation reduces the force by around 1,500 men to some 3,700 to 4,000.

We also posited that the legion may have marched alone, without the support of brigaded auxiliary regiments; units who may have been left in their forts to better control a clearly disturbed frontier zone in 117 AD.

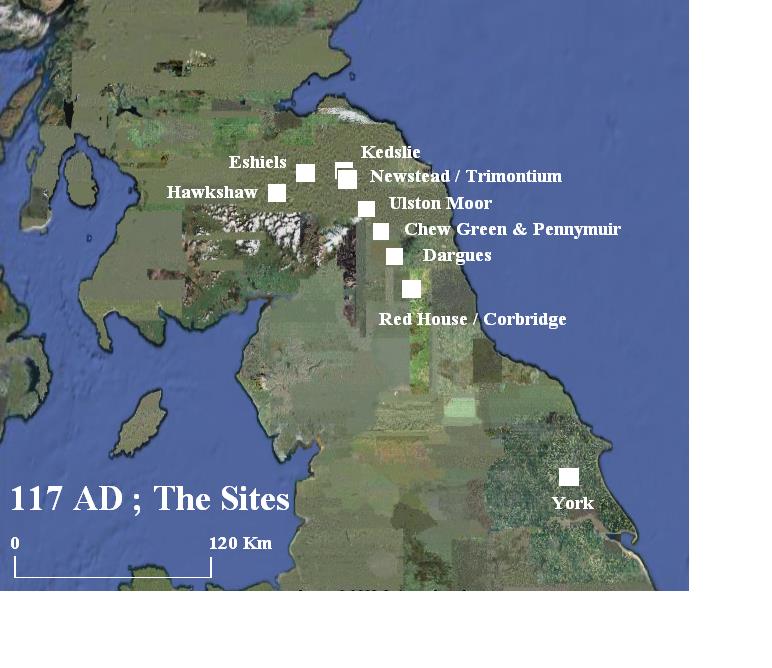

Secondly; as recent disturbances in southern Scotland appear to have penetrated into northeast England along the line of Dere Street (on a similar line to the modern A68) we suggested that this then is likely to have been one of the main areas of concern for Rome in Britain at this time.

Dere Street therefore is of continued interest in our search.

Identifying the likely culprits for the havoc dispensed in the early years of the 2nd C AD is no great historical whodunit, the finger usually being pointed squarely and convincingly at the Selgovae: the hill tribes of upland central southern Scotland.

This truculent tribe – or perhaps the name covered a loose confederacy of tribal septs – seems to have been an ongoing problem for Rome for most if not all of Rome’s dealings with ancient Scotland.

For example:

Certain forts built in southern Scotland during the first phase of the Antonine occupation around 140 AD – not least the reconstruction of Newstead on a grand scale with an unusual legionary/cavalry garrison- suggest that the territory on the edge of Selgovae territory was the problem that had either prompted Roman intervention or conversely was considered so acutely problematic at the time to warrant special treatment all of its own.

Further;

Later in the 2nd Century AD (following the withdrawal of troops from the mainline Antonine occupation) the Selgovae and their neighbours seem to have transmogrified into a tribal grouping known as the Maetae (link to the Tribes of Ancient Scotland article), a people who it appears caused Roman governors and the garrison of Hadrian’s Wall no end of problems in the late 2nd and early 3rd Century AD.

By 208 AD enough was enough and the governor pleaded for help from Emperor Septimius Severus. He in turn arrived with substantial reinforcements to bolster the beleaguered British garrison and campaigned first (in overwhelming strength) in Maetae lowland Scotland in 209 AD before then proceeding north against the Caledonians (with what appears a slightly smaller force). The Caledonians we are told had angered Severus by supporting the Maetae of southern Scotland.

Clearly, these years had seen something of a field day with all the tribes of Scotland taking a metaphorical pop at the neighbouring super-state and even more worryingly for Rome by showing a degree of unity of purpose in the process.

However, of greatest relevance to ourselves here is that the largest camps in Britain – the massive 160-acre sites in southern Scotland – are confidently attributed to these Severan Maetae campaigns and hint at the puissant threat Severus had to contend with in 209 AD. Indeed Cassius Dio and Herodian record the incredible losses that Severus’s army suffered to tribal harassment and the commonplace modern assumptions that locate these events among only the more northerly Caledonians are recorded nowhere in the historical sources.

The Selgovae and their associated septs and satellite tribes, for long the sackers of Roman forts, and a tribal confederation of noted and long-lived resistance to Rome seem therefore to be the most probable opponents that a suggested small(ish) Roman task force (such as we are looking for) would seek to chasten in a punitive foray, located within acceptable striking distance of Romes’ frontier – then situated on the Stanegate line.

Why should we not think that they advanced further north, against the Caledonians?

Roman intervention appears to have been infrequent north of the Forth – Clyde line, the frequency – based on marching camp remains – apparently decreasing the further north you travel.

It is fairly safe to assume that for much of – but not all – the twenty or so years of the Antonine occupation small forces could pass to and fro behind the Forth – Clyde running barrier in comparative safety as long as due diligence was paid in entrenching their overnight stops. And indeed this would appear to be confirmed by the small size of many camps commonly attributed to this time.

On the contrary and especially in the late period to which most camps in the far north belong -most camps here have the elongated proportions typical of late Roman marching camp morphology – Roman armies were staggeringly large, their camps rarely under 100 acres in size and often considerably larger. These are large enough to hold armies of well over twenty thousand men and in most cases considerably more.

To more fully appreciate this remarkable level of manpower and the enormous logistical muscle required for service against the Caledonians in the north of Scotland then a sense of scale is required through comparison

In England (and even Wales where we are told Rome met stiffer though equally short-lived resistance) the largest known marching camp is the Claudian invasion bridgehead work at Richborough – Rutupiae – postulated to be nearly 140 acres in size. This is unique and abnormally large for England and Wales where the main camps of around 20 acres are considered large, those around 40 acres very big and in a very few cases only those approaching the 60-acre mark are considered exceptional.

The great bulk of camps in England in particular are tiny, usually around 1 to 4 acres in size and cluster in the main behind Hadrian’s Wall. They are in all probability labour camps housing troops employed in the construction or rebuilding works on the wall that were undertaken throughout the Roman occupation.

Richborough’s suggested size is extremely unusual for the south of Britain; and is simply a reflection of the size of the original invasion force and the area required to accommodate its store dumps prior to splitting into separate columns to pursue and – fairly rapidly – defeat the tribes of southern England in detail.

This size of camp would not therefore be repeated and subsequent years saw a staccato through regular expansion, radiating out from the far southeast corner of England in steps between posts constructed from the start as permanent legionary fortresses.

The picture in Scotland – and particularly the north of Scotland – is much different and in the years which follow the period we are concerned with here, punitive military action was less the decision of governors and more the mandate of Imperial directive. Incredibly, on an amazing number of occasions, the ancient sources record direct intervention by the Emperor in person!

Indeed these were no sham show-boating performances like that of Claudius at Colchester. The large marching camps known in the far north of Scotland confirm that the armies that accompanied these Emperors were sized to suit Imperial prerogative and safety in a locality remote from the comfort and safety of the southern half of Britain.

While this speaks highly of Caledonian belligerency, as indeed do the even larger forces Severus brought to bear on the puissant Maetae of southern Scotland, it remains highly improbable that either the Governor or the Ninth Legions legate – even in a fit of foolhardiness – would attempt a penetration through hostile southern Scotland all the way to northern Scotland with such a small and unsupported force.

The events of 82 AD – when Agricola split his army into 3 smaller columns with near disastrous results – were never as far as we can tell repeated and as such it is unlikely that it was forgotten in a singular instance a mere 35 years later in 117 AD.

Further, it is not entirely without profit to ponder over the fate of numerous similarly sized southern armies of later ages who, engaged in raids in southern Scotland, suffered spectacular defeat at the hands of Scots, particularly when exercising insufficient caution such as at Piperdean, Cockburnspath, Sark, Haddon Rig, Ancrum Moor, St Monans, Skaithmuir, Glen Trool, Loudoun Hill, Lintalee, Benrig, Boroughmuir, Roslin and Nisbet Moor to name but a few.

And finally, to underline the point no Roman marching camps (currently known) survive in the far north of Scotland small enough to suitably accommodate the modest numbers we have suggested were involved in what we speculate to be the most probable scenario surrounding the loss of the Ninth Legion.

So our working hypothesis develops; a force of around 4,000 men advance into Selgovae territory in southern Scotland’s hill country along Dere Street to around the burnt-out husk of the fort at Newstead.

Curle’s investigations into the Newstead fort site in the early 20th century unearthed an incredible tally of abandoned Roman equipment buried on the site, dateable in the main to the fort’s destruction around 105 AD. These artefacts, now mostly held in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh are an amazing and very tangible “real” link to these days in Scotland, the very same period that some academics would have us believe we know nothing of! Nonsense!

How did the legion get there, and did they go beyond this?

To answer this we must look at the fossilised footsteps of Roman armies in time – the archaeological remains of marching camps – and consider if we can piece together a possible picture of the Ninths movement based on our 4 factors.

Obviously, not all marching camps remain to do this day, or their remains are so slight or elusive that they still remain to be detected. However, we need not shackle ourselves to the negative opinion of those who would claim that marching camps tell us nothing. True, they are notorious for the scarcity of dateable artefacts recovered in them, however as discussed in our Mons Graupius article several generally regarded “series” of camps can be deduced based on the camp’s morphology; i.e. its length by breadth proportions and some stylistic features – “clavicular” gates for instance (link to marching camps article).

Unlike Mons Graupius though we do not have the sure square or sub-rectangular plans of Flavian period works to rely on. This classic shape has a proven association with the earlier Flavian period (79 – 96 AD) campaigns in Scotland. They are datable by artefacts found in some key sites such as Carey but in the main by the archaeological structural sequence of certain key sites in relation to certain other more readily datable features such as roads and permanent forts. However, this Flavian camp morphology need not necessarily remain true for 117 AD, some 34 years after Mons Graupius.

Some small square or sub-rectangular marching camps – more accurately described as work camps- around Hadrian’s Wall can be attributed in many cases to the frontier defences original construction which commenced in 122 AD, a very telling mere 5 years after the troubled times we are concerned with here!

Some of the great-many other small camps here may belong to this time too, however, it is possible that many of these more elongated examples are the bivouacs of troops employed on any one of the great many later reconstructions of the mighty barrier following violent attack from the north as well as more mundane deterioration in its fabric.

So if these square or sub-rectangular camps do indeed belong to this period then it readily suggests that such forms may perhaps still have been the norm. However, we feel it is fairly safe to consider that slightly more elongated camps could equally be attributable to this period as well given the evolution in their proportions that camps underwent throughout the 2nd Century AD (as recorded by Pseudo Hyginus).

Writing his military manual much later in the 2nd Century AD he advocated tertiate proportions (1:1.5) to camps and suggested each legion (around 5,200 to 5,500 men) would require a mere 15 acres to accommodate them in such temporary works.

Hyginus’s figures are hotly contested though, his work is often considered to be an ancient theoretical desktop exercise that paid scant regard to the real-life practicalities of cramming such a large number of men, beasts and equipment into such small enclosures nor of reflecting the practical exigencies of armies on campaign.

What is known is that Hyginus’s work postdates the events of 117 AD.

Polybius’s older but more realistic calculation, which we reasoned was still in force during Agricola’s Flavian campaigns was less congested, giving a much more practical and satisfactory figure of around 25 acres per legion.

Finally, it should be noted that Hanson has suggested a figure of 335 men per acre, approximating to 3 acres per thousand men. This figure was not based on any ancient source; rather it appears to have been suggested in an attempt to reconcile the differences between Polybius and Hyginus’s figures. However, it still appears unrealistically small and as it is not supported by any reference in antiquity we shall leave that figure alone.

The safest route for us therefore is to continue following Polybius’s model in 117 AD though to acknowledge that innovations in camp densities may have come into vogue later in the century, particularly in the post-Antonine period.

Distilling Polybius’s 25 acres per legion arithmetically gives us:

25/5.5 = 4.5 acres per thousand men.

In the Eagle of the Ninth article, I suggested the Ninth may have marched north with a force somewhere between 3,700 and 4,000 men.

Using the rule of thumb above this force would require its marching camps to be in the region of 16.5 acres to 18 acres give or take.

(In the interests of fairness and for the benefit of Hyginus’s die-hard advocates the areas which can be extrapolated for this size of force using his suggested 15 acres per legion of 5,200 to 5,500 men would be in the region of 10 to 11 acres. However as mentioned above we feel this lower figure and density of camp was unlikely ever to have been achieved, even later in the century).

Further allowance should be made for a degree of discrepancy in the physical setting out of consecutive camp defences in any given “series”. Setting out after all in ancient times regardless of the surveyor’s handy rule of thumb ratios still remained firmly in the realm of “man in the loop” technology, entirely dependent on the soldiers’ ability to pace out the distance and direction accurately.

Such discrepancy is almost impossible to predict, but where lengths of camp defences take a distinct deviation in line – usually to miss difficult geographical features – then the actual area enclosed by the resultant camp defences will vary considerably from the area originally planned.

To compound matters, where high ground obscures the surveyors’ direct line of sight to all four corners of the camp then misalignment of these corners can be expected, a matter which increases the level of error in the camp’s constructed area compared to the surveyors’ original intended area.

So what camps are known that may suggest the route taken by the Ninth?

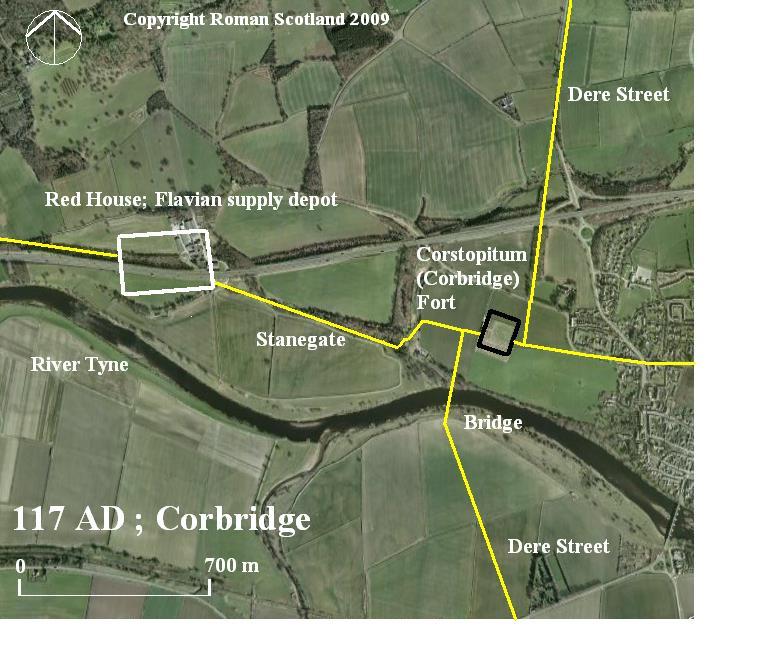

There is a dire paucity of marching camps of this size heading north out of the legions base at York (Eboracum). The trail therefore is effectively cold up to Corbridge (Corstopitum). This noteworthy Roman station is located at the crossroads created by the crossing of the lateral Stanegate road with the north-bound Dere Street after it bridged the River Tyne. However, at this time the post was simply an auxiliary fort.

Rather interestingly it had been built by members of the Ninth Legion to replace the earlier Flavian fort on the site which appears to have been devastated during Aviragus’s successful invasion of Roman Britannia in or around 105 AD and is a nice link with the unit we are concerned with. The Corbridge hoard, a chest containing scrap iron, is dateable to this period, and it is on the basis of this find that it is possible to reconstruct Roman Lorica Segmentata armour of the late 1st Century AD. The hoard and its loss is yet another nice and very tangible link with the years we are looking at.

Lying only a short distance to the east of Corbridge lay the remains of Agricola’s supply station at Red House, built to supply his advance into Scotland in 79 AD and the years of campaigning that followed. It appears however to have been abandoned fairly soon after this, and certainly by the time the first Flavian fort at nearby Corbridge was built around 90 AD.

At 25 acres Red Houses’ ramparts could conceivably have been pressed into service as shelter, however, the lack of marching camps to the south of here would appear to suggest peaceful conditions in Brigantia, a situation that may have merited nothing more defensively formidable than a perimeter of timber stakes.

This distinctly minimal level of security would merely prevent unauthorised coming and going and discourage petty theft. All of which is indicative of the peaceful conditions prevailing in the north of England.

North of Corbridge matters rapidly change. Brigantian tribal lands or hegemony extending north of the Stanegate (later Hadrian’s Wall) has been much speculated and certainly greatly overstated.

What is certain is that by the time our column of troops reached High Rochester (Bremenium) they were deep in Votadini territory.

(Note; the current Brigantium archaeological reconstruction centre here is misnamed.

The information contained in Ptolemy’s map (link) lists Bremenium among the lands of the Votadini.)

Before this, however, the force passed the Roman station at Habitancum. The fort here – Risingham- is probably a later construction while the marching camp (West Woodburn) at 27 acres (and most probably squarish in plan) is likely to be either contemporary with our period or belonging to the earlier Flavian one.

Notwithstanding this, at around 27 acres the camp is too large for us so our force marches on until, near the currently undated fort at Blakehope on the River Rede we come across our first serious candidate site for our force’s overnight stop; Dargues.

The marching camp at Dargues has tertiate (1:1.5) proportions. This may raise some doubts about its applicability to the period we are looking at but as it is no more elongated than that we will tentatively accommodate its identification in our list of sites the legion may have used.

Its size; 14.8 acres is of interest, if marginally too small. There are however no notably difficult features on the site that may explain an error in setting out. Further, it is close in size to another group of camps of around 13 acres in size that we shall meet time and again so it remains possible that the camp may be part of that group – particularly as that series contains more camps of classic tertiate proportions than we should perhaps anticipate in 117 AD. Tentatively, however, we will note this as the first halt of the Ninth after leaving Corbridge – some 20 miles or so (a good days march) to the south.

Across the River Rede lies the field of Otterburn, a scene of no less violent and calamitous conflict some 1271 years later when the Scots under Douglas crushed Percy’s larger army in a vicious moonlit battle in 1388 and frightened off the militant Bishop of Durham’s equally large reinforcement army the following day.

The local tribe, the Votadini, are not in general terms thought to have been at loggerheads with Rome; however this territory, skirting the looming high ground is worryingly close to the likely lower reaches of Selgovae territory and here the Romans – near bandit country- looked rightly to their defence when encamped at night.

From Dargues the Roman road heads high; ever northwestwards into the wild area around Otterburn training grounds. No camps here match the size we are looking for.

Not even at the abandoned or sacked Flavian fort at Bremenium (it likely shared Corbridge and Newsteads’ fate in the fighting of 105 AD) do we find one, and although it is ringed by marching camps of many styles and likely dates none match our criteria.

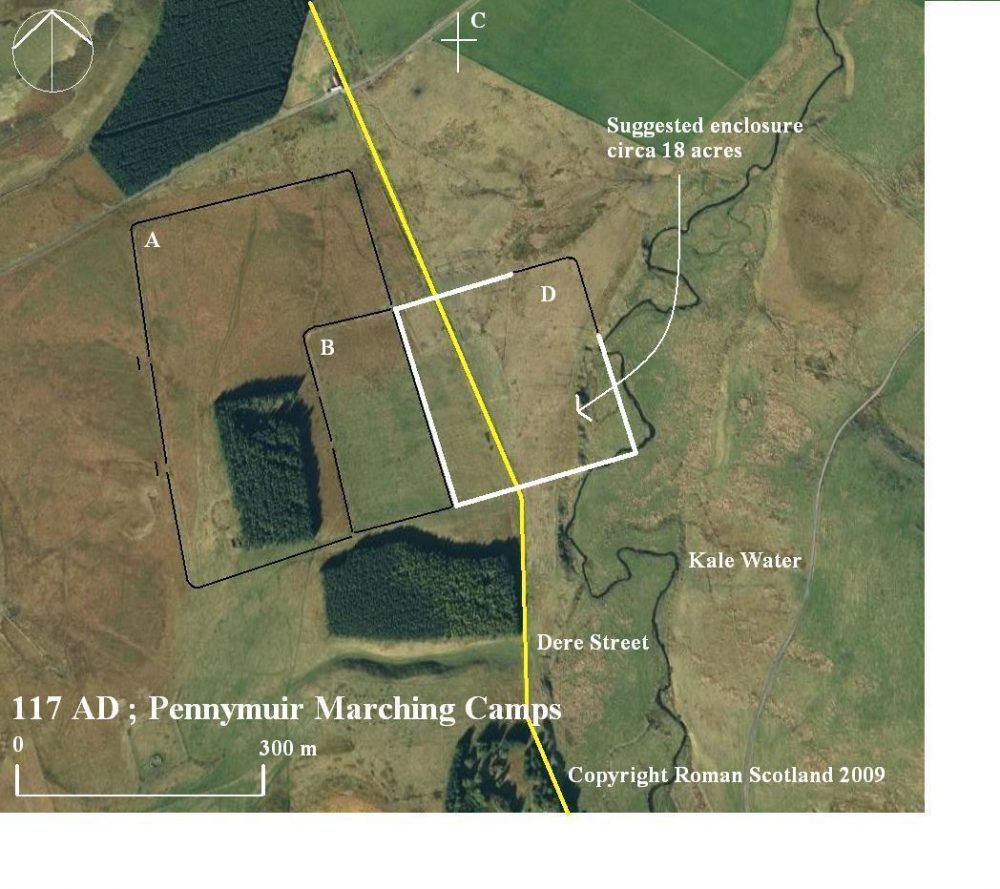

So onward our force marches till at the extremity of the Northumbrian National Park we come across the remarkable little Roman station at Chew Green, and, some 5 miles to the northwest across the modern Scottish border the matching grouping of marching camps at Pennymuir.

The log jam of camps at these sites offers a very interesting investigation for us, the sites being located on either side of difficult high ground (above 400m OD) in the Cheviots.

As such these camps – not unlike modern motorway service stations – will have seen continual reuse so we should be careful about suggesting that any camp belonged to the movements of our footsore column coming up from Dargues (10 miles to the south over demanding ground) and no-one else.

That said, Chew Green has two marching camps of note. That of particular interest is an almost square camp measuring in at just below 19 acres. This is effectively within our broad target range of 16.5 to 18 acres “give or take”. This camp in all probability was built during the earlier Flavian period due to its square proportions and its clearly early position in the multi-period sites’ “structural sequence”.

If reused then we can add Chew Green to the road map of our suggested march of the Ninth.

Before we move on it is worth casting an eye over the other camp here, the 13.75 acre marching camp. This size of camp is below our target range. The camp is also slightly more elongated than the 1:1.5 tertiate proportions mentioned above. It is reasonably safe therefore to attribute this camp to a later period and acknowledge that it will have likely been reused on many occasions.

The short hike across the Cheviots here, coming down next to the mighty Woden Law escarpment is difficult but under the circumstances perhaps insufficiently challenging for a Roman column – now undoubtedly deep in enemy territory – intent on a fast penetration to stop over for the night. Therefore we could be forgiven for overlooking Pennymuir, the mirror-image location of Chew Green.

Pennymuir has some impressive upstanding remains, yet on first appearance seems to lack a camp of the size we are looking for.

However, an interesting structural relationship can be seen in camps A, B and D.

We suggest that a tentatively reconstructed camp D is earliest- and Agricolan- as it would underlie Dere Street which would have been built soon after his invasion of 79 AD.

Next on site is camp A, and due to its proportions it is fairly likely that it has an Antonine foundation date. In keeping with this timeline it respects Dere Street but overlies a portion of the underlying Agricolan.

This overlap portion is then reinforced in a later reuse of the site giving us camp B. Is this the end of the story for us at Pennymuir?

Perhaps not.

As already mentioned the Ninth may have pressed on without stopping after descending from the Woden Law escarpment, especially if they were marching fast on a lightning campaign. However, on the basis of our understanding of the likely structural sequence at Pennymuir outlined above there remains an interesting possibility.

In 117 AD all that would have been on the site was the remains of the large Agricolan camp, with Dere Street rather inconveniently bisecting it. For the sake of discussion however, if the Ninth were to have made use of that portion of the camp to the east of the line followed by the later camp A (perhaps even sharing a rampart) then rather interestingly the area this would appear to enclose (the erosion to the south-east by the Kale Water is later) would be close to our target area.

So at best all we can say is that the Ninth could have camped here.

Onwards our force proceeds and regardless of whether they stopped at Pennymuir or not the next station along the line is of great interest. Cappuck near Jedburgh is yet another site with a fine tally of marching camps and has one close to our target area. The small fort here has attested use (deduced from finds) not only of the Flavian and Antonine periods but crucially also from the late Flavian/Trajanic period – exactly the period we are looking at.

Was this therefore a halt of greater urgency than the simple expedience of an overnight encampment? Or had the unrest which drew the Ninth Legion north seen an outpouring of Selgovae violence at Cappuck?

We can not know with certainty but it is a compelling thought as well as reminding us – as indeed our ancient colleagues in the Ninth would have been presciently aware – that they were now operating deep in a dangerous country, a land where the Selgovae campaigned with confidence.

The marching camp of interest here – “Cappuck 1” on Ulston Moor – is just that tiny bit large at 19 acres but similar in area to the early camp at Chew Green which we have already suggested the Ninth may have used. The camp’s proportions are tertiated – and therefore later than the early Chew Green camp’s original construction.

So at least we may posit that if the Ninth did stop here they may have been the builders of the camp as opposed to simply making fortuitous re-use of a pre-existing camp such as Chew Green. For the purposes of our investigation therefore we give Cappuck 1 a tick and set off again north along Dere Street. At St Boswells a camp of over 12 acres sits by the Tweed, another example of the slightly smaller group of around 13 acres already encountered.

Soon Dere Street passes the major Roman complex at Newstead (Trimontium) near Melrose, lying in the lee of the prominent Eildon Hills. The fort here, sacked some 12 years earlier would remain a focus of Roman attention throughout the busy 2nd C AD, particularly around 140 AD when Pius had it rebuilt, giving it substantial defences. However there are no marching camps of the size we are looking for here, so we must press on.

And at this point, we ask ourselves a very relevant question, where would the legion be pressing on to?

The monster 160-plus acre camps of Severus’s later Maetae campaign – the likes of which can be found absolutely nowhere else in the British Isles – certainly proceed north from here towards the Firth of Forth.

Another road however has long been sought hereabouts; the one that passes “from Newstead” westwards along the Tweed and eventually Lyne valleys. The eastern portions of this road have long been sought around Newstead with no success. That the road did exist is proven by its known western elements and the multi-period fort and campsites along its route. This proves the region constituted an ongoing area of concern and campaigning for Rome.

These hills and valleys also hold the remains of considerable Iron Age tribal activity and it would be disingenuous to suggest that with such close Roman supervision being the order of the day over several periods these settlements and hillforts were not inhabited in the Roman period. The area therefore was in all likelihood one with a major Selgovae tribal focus and the find spot in this general area of the Hawkshaw head confirms less than cordial relations with Rome here at this very time.

But where exactly did the westbound road go from Newstead? That question has long vexed academics. Could the marching camps of our suggested route taken by the Ninth Legion offer a solution?

I think so.

Newstead controlled Dere Street’s crossing of the Tweed and it is possible that the crossing here was by bridge. Following Dere Street north from this crossing (the same north side of the river it should be noted upon which the known portions of the westbound road runs) we soon encounter the marching camp at Kedslie near Earlston.

This camp has no upstanding remains and is known only from aerial photographs. It is however of significant interest.

It sits a mere four miles north of Newstead so perhaps that explains why no halt is recorded there. At 20 acres it is again marginally larger than our target size and again, like Cappuck has proportions close to tertiate.

However this camp offers the point at which a plausible junction may have existed between the northbound Dere Street and the mysterious westbound road, and indeed the lie of the land here as well as further west would appear to corroborate the possibility.

Before we follow this line however we must ask ourselves if any camps exist further north along Dere Street which would suggest that the force which marched and camped in these camps did not turn west here into the difficult ground of Selgovae territory.

To the north, close to the Firth of Forth at the Antonine period complex at Inveresk are the remains of a camp of 20 acres (or larger) has been identified. This makes partial re-use of the large Flavian/Agricolan enclosure there. Could this have been a terminal destination for the troops who used Kedslie?

Possibly, however, given Inveresks’ pivotal role in the later Antonine occupation, it seems most likely that this enclosure dates to that period. Further, and most tellingly, Inveresk lies squarely within friendly – or at best- less hostile Votadini territory than that occupied by the truculent Selgovae.

If the Votadini were the intended recipients of Roman punitive action then the settlement on Traprain Law near Haddington in the Lothians is unlikely to have enjoyed the unbroken occupation that archaeology suggests it did. This is quite unlike the treatment meted out in Selgovae territory; the incumbents of the oppidium on Eildon Hill north for example appear to have been ejected to make way for a Roman signal station.

No. The Inveresk camp probably records activity later in the Antonine period, and whether its builders came via Kedslie cannot be guessed with certainty though reusing earlier structures would be just as viable a proposition for troops in the middle of the 2nd Century as it would for those in 117 AD.

So west we turn towards the known stretches of Roman road further along the Tweed valley, following easy high ground (usually much favoured by Romans when setting out their roads) via Langshaw, Colmslie and Buckholm to the old crossing of the Gala Water at Torwoodlee above Galashiels.

By now we can safely assume that the Ninth, now deep in Selgovae heartlands, were busily meting out devastation upon the unlucky natives, an approach clearly repeated by invaders from the south in a later era given the number of ruined tower houses hereabouts.

Once across the Gala Water – following the natural corridor in the lie of the land – it is a fairly straight line via Caddon Mill at Clovenfords (the name ford is an apt pointer when looking for old roads), down again to the northern bank of the Tweed opposite Peel, possibly following a broadly similar line to the modern road here.

Whether the Roman road followed the Tweed close to its north bank (as does the modern highway) or further uphill is uncertain. Difficult terrain such as the constricted ground where high ground comes down close to the rivers northern at places like Thornielee and Pyat Hill would tend to suggest the former.

At Innerleithen, we pass the marching camp situated here. Only part of this camp is currently known though the positions and lengths of these ramparts and gate suggest that this camp is probably larger than our target area.

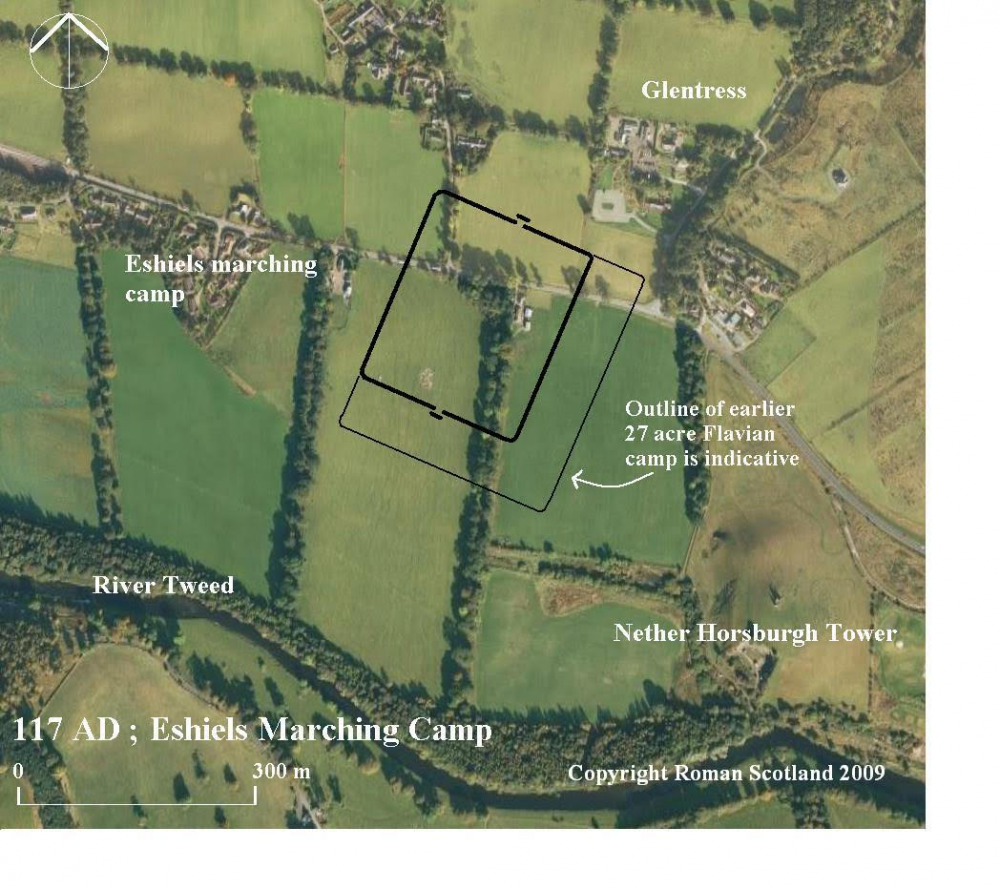

It belongs then to one of the many other Roman forays into deepest Selgovae territory. The camp’s position does however confirm that we are indeed on the line of the Roman road, especially as within a few miles further we come to a site of the greatest interest in our quest; that at Eshiels near Peebles.

Eshiels, lying on the north of the Tweed has two camps. The earlier is an almost square camp complete with clavicular gates and measures over 27 acres in size. We can reasonably date this camp therefore to the Flavian period, most probably to Agricola’s campaigning in central southern Scotland against the Selgovae in 80 AD.

Inside this camp is another. It reuses the earlier camp’s western side and at 16.3 acres – capable of accommodating around 3,600 men – it sits well in our target range. The period we are looking at remains sufficiently close to the Flavian period for camp defences of that period to remain upstanding, and as we have already pressed the Flavian enclosures at Red House and Chew Green into service by our suggested route taken by the Ninth Legion then reuse of parts of the defences of the earlier camp at Eshiels is just as possible.

This camp measures some 280 by 236 metres, giving a proportion of 1:1.18. This is more elongated than square yet less than tertiate proportions so fits into the constraints of Roman marching camp morphology at the period we are concerned with.

And tellingly, at that, the trail goes cold.

The earlier force that built the first camp at Eshiels clearly carried on down the Tweed and Lyne valleys as their next stop is the matching-sized camp at Lyne; a site that was also used as a stopping-off point most probably in the Antonine period.

And further along at Wester Happrew, near the roads probable fording point across to the Lyne Waters southern bank we have another of the 13-acre camps; the series which has shadowed our footsteps throughout this journey.

This series is not finished and clearly marks the progress of a Roman force that seems to have travelled (probably in the Antonine occupation period) safely onto Castledykes at the far edge of Selgovae territory.

Our camps, the group of 16.5 to 18 acres -give or take- stop abruptly at the second camp at Eshiels, suggestive (unless other camps come to light in the future) that either the force who campaigned here turned about and marched back the way they came or, more prosaically, disappeared.

This clearly is of immense interest to us when searching for a legion – that one stationed to safeguard Romes’ northern frontier in Britain- which disappears from the historical records at this time; a period of recorded strife in southern Scotland and one where Rome is recorded losing many men.

Further, analysis of the ground here is of interest.

In our search for the locations of Agricola’s activities in the year preceding Mons Graupius (link to Mons Graupius 82 AD Addendum) we highlighted the probability of Dalginross near Comrie on the River Earn being the scene of the stiff fighting when the Caledonians made a night-time assault on the marching camp of one of Agricola’s three detached battlegroups. Interestingly that one was also based around the Ninth.

Dalginross lies in a natural bowl, surrounded threateningly by high ground on all sides. It appears to have been both a suitable proposition to tempt the Caledonians to mount an assault on that occasion as well as a sufficiently problematic hotspot for Rome to subsequently make repeat attempts to control it by maintaining a garrison there.

The similarities with Eshiels are pronounced.

The terrain surrounding the marching camp at Eshiels is also very suitable for the Selgovae to have confronted the Romans. The marching campsite here is threatened by high ground – comprised of Kirn Law, Kittlegairy and Cardie Hills- to the north; the Glentress outliers of the Moorfoot Hills. Many of these, and the surrounding heights, are crowned with tribal forts and settlements.

Whether the Ninth was assaulted in its camp at Eshiels or ambushed while strung out on the march after leaving the camp (the ground to the west below Smithfield would be ideal) we cannot know. Reading the ground however, it is clear that no matter the manner in which the Ninth came to grief, they had, by marching to Eshiels, placed themselves in a position from which it would be extremely difficult – given the circumstances perhaps nigh on impossible- to extract themselves back along the route they had come.

A classic ambush is made upon the flank of an opponent and incorporates “stops” at the extreme ends of the ambush (or beyond) to prevent any of those attacked from successfully escaping.

Looking at the ground to the west of the native settlement at Ven Law above Peebles it is clear to see the easier terrain towards which the Romans were ultimately headed – if they continued to follow the Roman road – and to which the tribes may have been equally keen to completely block their access to.

So the intriguing scenario offers itself of the Ninth being overwhelmed in the main either in their marching camp at Eshiels or below the heights of Smithfield.

Any retreating remnants of the Ninth may have been either unable or were annihilated in the process of attempting to force passage at the choke points on the road below the towering high ground at Lee Penn and further to the east at Pyat Hill.

Indeed it should be noted that under not dissimilar circumstances to those we have suggested here, Varus’s force in 9 AD at the Teutoburgerwald seems to have been dogged and worn down by the Germans over the course of several miles (in markedly less demanding terrain than we suggest here).

Poignantly, next to the Eshiels camp sits the spur of high ground on which the ruinous stump of the tower of Nether (or Over) Horsburgh now stands. This is advantageous ground, protected in part with precipitous falls and offers itself as a suitable defensive position upon which fugitives from the main action, or any failed attempts to escape east, may have regrouped.

Any scattered survivors who managed to cross the tweed would have been faced with a perilous journey back through a difficult country swarming with vengeful natives. Few if any are likely to have won through.

As such, taking our hypothesis over the location of the loss of the Ninth Legion to a conclusion, we may speculate that Nether Horsburgh is the best location where – ultimately – the desperate last moments of the remnants of the Ninth may have been played out.

Finally, where exactly may the Ninth have been heading to before possibly coming to a sticky end in or around Eshiels?

To the west of Peebles a Vicus (Roman civil settlement) had sprung up in the earlier Flavian occupation at the fort of Easter Happrew at the junction of the River Tweed and the Lyne Water.

There can be little doubt this had already been abandoned before or sacked during the earlier events of 105 AD, however, it may – as a known Roman site, perhaps Ptolemy’s Calonica (Colonica in Latin rather significantly means colony) – have been the planned limit of the Ninth’s punitive action, and certainly a site which the abrupt termination of the series of suitably sized camps at Eshiels suggests the force that camped there fatefully never reached.

Conclusion

We do not have a detailed account such as Tacitus provided in our search for Mons Graupius to assist so we absolutely cannot say the case for Eshiels is proven beyond doubt.

However, it is thought-provoking that a series of camps of a size suitable to hold the numbers we have suggested may have marched north in 117 AD terminates so abruptly in an area of notably heavy tribal occupation and repeated Roman campaigning – as the many other camps and forts in the area prove.

Further, Eshiels lies a mere twelve miles as the crow flies from the Hawkshaw Heads find spot further up the Tweed at Tweedsmuir; an interesting and contemporary snippet of history (link to article) that may be in some way loosely or perhaps even intimately linked with events discussed here (Percy it should be remembered came to grief in 1388 at Otterburn attempting to retrieve both his captured standard and damaged honour from Douglas).

Pending any artefactual findings by others in the future this all must remain a speculative working hypothesis but it is the nearest to a location we can identify where the Ninth Legion – the IXth Hispana – may have ultimately encountered its fateful date with destiny.

And when compared to the complete guesswork – struggling to swim against the tide of probability – of those vocal few who claim the legion was lost somewhere other than Scotland (on no evidential basis whatsoever) it becomes a compelling proposition indeed!

Epilogue

And finally, where could the Eagle standard of the Ninth Legion be sought?

Sutcliffe’s novel was the first reference to the missing standard, however, it was a reasonable suggestion that the standard would be lost with the missing legion and the artefact itself has long become the stuff of legend.

Could this artefact be found?

We do not know, we are not treasure hunters, but it is fair to say that several related items; the Hawkshaw head and the magnificent cavalry face mask helmets at Newstead are contemporary with this period.

These relics have, to date, been looked at abstractly and individually by academia. However when pulled together as a body of material – of the very time we are concerned with – then they paint a telling picture of totemic Roman artefacts, looted or won as spoils in war and apparently ritualistically deposited in Selgovae dominated southern central Scotland.

These assembled artefacts certainly act as wayfinders, pointing ominously to the location of the tumultuous events of those years. They would then seem to point quite clearly to the region where a carefully managed search may one day succeed in unearthing the one single artefact which would finally put to rest the whole mystery surrounding the loss of the Ninth Legion; the IXth Hispana.

For those seeking such closure herein lies the hope for the future.

First published in 2009 on RomanScotland.org.uk