Myth and fable surround much common understanding of Roman roads, they are for instance proverbial for their straightness and all lead to Rome. Or at least so we are commonly told. The purpose of Roman Roads in Scotland was to facilitate the movement of troops and supplies, Roman Scotland being primarily a military affair.

In the first year of Roman campaigning in Scotland, no roads as such existed. Many books give a very misleading impression of the nature of a Roman army marching on campaign, especially concerning roads. These often show a Roman army marching in column, like a veritable colony of ants on the move with engineers preceding it creating a ready-made road for the troops behind to march on. This is a very misleading picture.

When operating in Scotland the Roman forces will at first have traveled literally across country with the pioneers’ task being that of clearing the route of the worst obstacles. This could involve a level of tree removal and also a matter of throwing small temporary bridges across the many burns and streams that would otherwise have made the journey of infantry and particularly the carts carrying their heavy equipment and supplies an extremely slow and arduous process. It is in the later consolidation phase that proper roads will have been constructed in over-run territory.

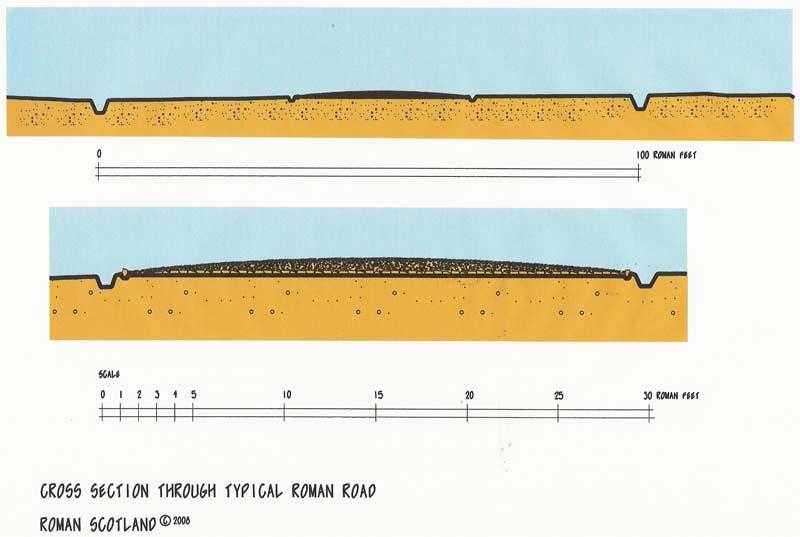

The standard road – there were of course variations – relied for their construction generally on materials immediately or available readily close to hand. In Scotland, unlike the Via Appia in Italy, the road was not paved with stone slabs. Its surface was of small gravel, well rammed to give a “metalled” wearing course which was bedded on a series of layers of gradually heavier aggregates, then stones, sometimes the whole affair having a bottoming of fairly substantial rocks. This was formed over the “natural”, in other words, the virgin earth once cleared of vegetation and turf (illustration No. 1).

The roads often, therefore, sat up from the adjacent ground level, this raised running mound of earth being termed an “agger”, The height of this structure is the root of the relatively modern phrase “highway”.

At the edges of the road build-up, the Romans often set fairly large kerb blocks, and it is often the roads where this good practice was undertaken (and assuming the kerbs were not removed for later reuse by locals) where the agger remains can best be seen today. Without kerbs the build-up often eroded or washed away under the pluvial onslaught of Scottish weather.

The roads were generally wide enough for two carts to pass each other. In the east, the main trunk road latterly known as Dere Street (it approximates to the modern A68) was thirty feet wide. This was exceptional in Scotland and most roads were narrower, being around twenty feet wide.

To combat the unpredictable Scottish weather gullies ran parallel on either side of the agger and these took surface water runoff from the agger which in cross-section was normally cambered like a modern road. Beyond the gullies the vegetation and trees were cleared back for security. In the empire this cleared zone was delineated at its extreme edges by further ditches -though finding these outer ditches has been, to date, little investigated in Scotland. Within this cleared area – which was around a hundred feet wide were the pits that were dug to extract the gravel and stones required to form the road.

In locations where “normal” road build-up materials were naturally scarce or where the ground was excessively boggy other tried and tested road construction techniques were employed. These, often relying on a “floating” timber rafts of split logs and branches rarely survive well, the damp conditions prevalent in their setting contriving to ensure most traces of the road have long since rotted away. On sloping ground, an artificial terrace would be formed, as ever the key being to equalise the quantity of cut and fill in the exercise. These are often termed “lynchet” ways.

Roads deteriorate both with use and through time. Now it is often the gravel pits or “scoops” as they are called which give any clue that a Roman road passed any particular way. These now either appear as crop marks in arable countryside when viewed from the air or as indentations in the ground. Quite often small quarries in the countryside echo the original quarrying by the road work gangs which have been further exploited in later times often for the same purpose.

Roads were usually set out on a point-to-point alignment by surveyors using the surveying device called a “Groma”.

Although short stretches of road are indeed synonymous with proverbial straightness it was often at the surveyors station (usually on high ground) that changes in the roads point to point alignment takes place. One of the best examples of this can be seen at Wishaw in Lanarkshire, where the towns main street overlies the Roman road and where a change in alignment is recorded in the modern road layout outside the Auld Parish Church. This is near to the aptly named Imperial Bar where the irrepressible humour of the locals has it that the Roman surveyors retired to for a pint after setting out this section of the road!.

Visual aids to this surveying technique were essential and it can be of little surprise that many roads in Scotland seem to aim for conspicuous hills.Without doubt, however, of the archaeological record of Roman Scotland, it is in respect of roads that least is known. This is on account of several factors:

Firstly, given the nature of the hilly countryside in Scotland, most Roman roads ran along courses which were subsequently reused by medieval hollow-ways and roads of the industrial era – including military roads in the north. Into this congestion add later works such as modern roads, farm tracks and field boundary features, canals, railway lines or the fact that the original road now lies beneath modern towns and cities. Whole stretches of the Roman road network, therefore, have been obliterated with little chance of recovery. Little surprise that little is known of Roman roads under cities such as Edinburgh and Glasgow where remains of the original road which certainly existed are long lost.

It is often where later features, such as field boundaries with their ancient hedgerows, farm tracks and modern roads with an ancient pedigree reflect the underlying original Roman road that evidence can be brought together to suggest the possibility of a Roman road in any given location.

The road’s purpose, as noted above was to expedite the movement of troops and equipment to certain points, usually permanent forts and settlements as well as frontier installations and harbours.

Following the trend of roads in England where north-south roads ran either side of England’s hilly central spine, the main Roman roads in Scotland enter as extensions of these thoroughfares; in the east at Pennymuir near the modern A68 and in the west near Carlisle near the modern M74. It is probable a third main route entered Scotland, possibly bridging the Tweed at Tweedmouth on a similar if not the very same line as the medieval bridge at Berwick. Further indications of this ephemeral road in the coastal Lothians are anticipated in the future.

Between these main north-south routes lateral roads made connections to and from key Roman forts.

At present, our knowledge of Roman roads in Scotland is very fragmentary and is not understood at all north of the Tay. Antiquarians famously noted Roman roads at many locations, often incorrectly – however a clear understanding of the Roman road network in Scotland has not been assisted at all by an unfortunate modern academic trend. As highlighted by one respected author this involves academics seeking an easy fame (or notoriety) through indulging in a negative approach where carefully selected locations aimed to yield the desired outcome are dug with the intention of proving a Roman road “did not pass this way”.

An opinion frequently trotted out to explain the resultant sparseness of Roman roads on the map in Scotland, the undoubted tangible result of decades of this negative approach is that the Romans gave up on their road-building programme in any one of their many incursions in Scotland before any particular road could be built or completed. This is a very unsatisfactory suggestion that does not acknowledge the intent of Imperial strategy, itself entirely reliant on the benefits afforded by good and ready communications.

No matter the back-breaking nature of the work Roman roads will have been put together speedily during the summer season and instances of the work squads downing tools on the receipt of fateful orders to evacuate after what were fairly lengthy periods of time “in-country” will be the extremely rare exception, not the general rule.

There can be no serious doubt that the Roman road network will have passed north of the Tay. A bridge is recorded at Bertha on the Almond proving northwards communications. The oft-cited opinion that no land route linked the installation below and above the Tay is farcical, not least as one of those northern installations was a full legionary fortress. In the phrase used by pro-active archaeologists; the current lack of available evidence need not necessarily be taken as evidence of omission in antiquity.

The quest, therefore, continues to pin-point the route(s) to permanent installations north of the Tay among others.

Identifying Roman roads is a particularly interesting subject, not least as the discovery of a new stretch of road quite often points the way quite literally to discoveries of the installations the road was leading to as well as features along the way. Some of these features can be bridges and fords.

Crossing waterways was a major consideration to any communications within ancient Scotland. Ideally roads headed to points where local information provided intelligence that larger water tracts were fordable all year round. A river that was fordable only during the summer for instance was not good enough for obvious reasons. The Romans where possible preferred to use suitable fords as large bridges were vulnerable to guerrilla action and took time to replace – time a relief column for instance could not afford.

Smaller burns could be simply bridged quickly and this is likely to have been the common solution to roads crossing the many smaller watercourses in Scotland. Most of these have cut distinct rills and gullies and are deeper than they are wide and which unbridged would have constituted a considerable obstacle to traffic, either on two feet, four feet, or wheeled.

Such minor works would not have required the substantial structural abutments synonymous with larger bridges, something that explains the lack of remaining archaeological evidence of such small bridges’ existence.

Fords were often paved, but understandably given almost two thousand years of active water action the paving seldom survives. A give-away to a Roman crossing however often comes in the form of a scattering of small finds in the water at fords, usually small coins offered to propitiate the local spirits by the Romans who were famously superstitious.

While Roman roads were kept as level as possible, it is generally on the descent to fords that gradients on Roman roads are at their greatest, Indeed in the approach to fords, the Romans often created a zig-zag of switchbacks to lessen the gradient to a maximum generally of 1 in 6 (16%). This substantial gradient was still too much it appears for later wheeled traffic and it is often at these approaches to fords where Roman roads best remain unaltered by later roads which tended to take a more circuitous and easier approach to a ford.

These gradients in themselves have prompted interesting discussion that Roman roads were used less for the movement of heavy supplies than would be thought at first, such gradients being extremely difficult for ox-drawn carts. River communications, therefore, still little understood as yet in Scotland, undoubtedly played a central role in the transshipment of bulk supplies to forts and armies on the march.

Roman forts are often found in proximity to where roads crossed a river or large stream and may have been located there to protect a bridge – it was not always practical to ford a river- as well as being able to supervise and perhaps control the movements of the local tribes at these strategic locations. No Roman bridges remain in Scotland. The many commonly “named” Roman bridges in Scotland date to the late medieval period at the earliest and often to even later military periods in the north.

Sometimes however a medieval bridge, such as the packhorse bridge next to the fort at Bothwellhaugh in Lanarkshire in some respects deserves its title as the “Roman Bridge” as it fairly certainly occupies the site of its ancient predecessor. Figure 5 shows an antique print of the bridge with natural water levels of the South Calder prior to the inundation of the adjacent man-made loch at Strathclyde Park.

It is usually assumed the Romans constructed the roads themselves. Road construction is a back-breaking task, the majority of the work however once the main decisions on route and form of construction was agreed was unskilled labour and in “The Agricola” Tacitus puts in the mouth of the Caledonian warlord Calgacus the northern tribes’ grievance of being forced to work on Roman Roads.

There certainly will have been a duty imposed where possible on the local tribes by the Romans to maintain sections of the roads within their tribal areas, one of the many levels of taxation the Romans could burden the locals with. Whether this was the case during the consolidation phase is not known but we should exercise caution in distributing too much of the garrison employed for long periods of time constructing roads in dangerous remote locations when cheaper labour – for the conquerors at least – was readily to hand.

Article first published May 2008 (romanscotland.org.uk).